Throughout history, there have been many examples of intense division; Roundheads versus Cavaliers, North versus South, Beatles versus Stones, Leave versus Remain, Laurel versus Yanny, the list goes on.

But few subjects will have inspired the kind of fierce debate than the question of which is better for making FPL decisions; Stats or the Eye Test.

Proponents of the Eye Test; the idea that you need to actually watch football to do well in FPL, or at least that it is beneficial, often view Stats aficionados as nerds and somewhat artificial football fans who would probably be playing Fantasy K-Pop as long as it involved a pivot table.

They are often heard saying things like “Do you even watch football?” in a pejorative tone towards huddles of Stats fans, nervously and nasally talking ‘xG’ in what they believed to be an FPL safe space.

Supporters of Stats; the opinion that underlying statistical information provides as good if not better view of football for the purposes of making FPL decisions, view proponents of the Eye Test as knuckle-dragging luddites who probably own a Greggs rewards card and reminisce for the ‘glory days’ when watching Saint and Greavsie on a Sunday afternoon was enough FPL research to give you ‘that edge’.

Okay, so all of this is maybe a little hyperbolic for the purposes of creating dramatic tension and, in reality, we all probably sit at least a little across both camps, but the question does remain as to which is better for making FPL decisions; Stats or the Eye Test and this is the question I’m going to try and address here.

The Eye Test

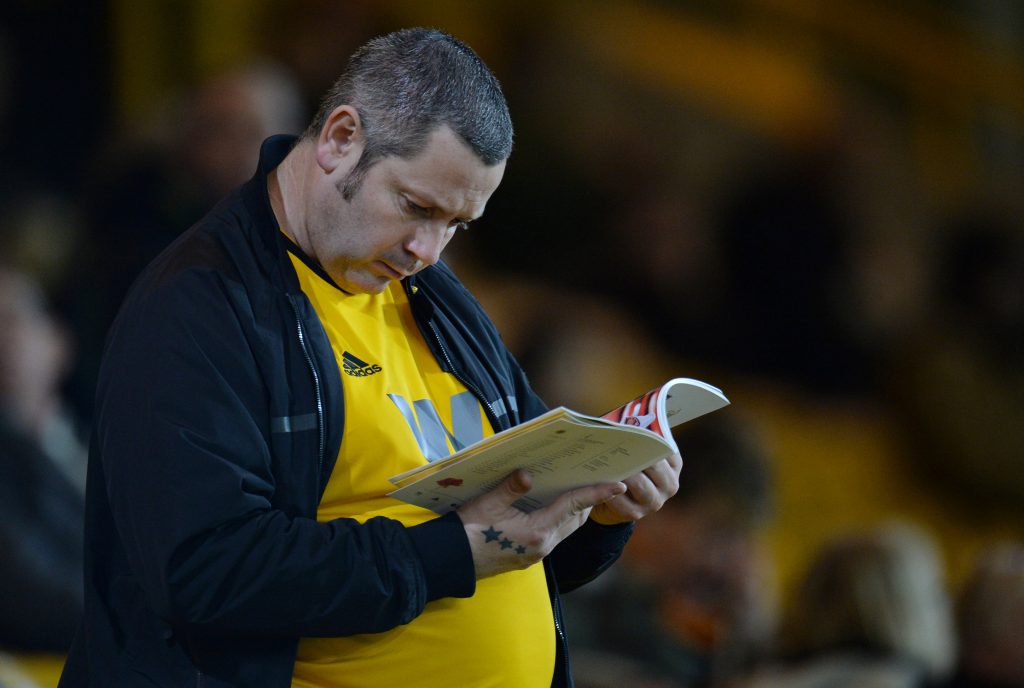

You would think that watching football would be an obvious benefit when it comes to playing a game that involves making football-related decisions and, indeed, many of the best FPL players out there, and several FPL champions no less, credit their success to the amount of football they consume.

It’s true that watching football can offer a lot to your FPL game as it provides the viewer with a broader understanding of football tactics and strategy and how these function, interact or conflict in order to increase or decrease a player’s chances of scoring FPL points.

Much of this is often difficult to pick up in stats alone, an example perhaps being Leicester’s Jamie Vardy (£9.7m) and his famous goal-scoring runs of the past, which occurred despite him seemingly taking barely any shots on goal.

The manner in which Leicester played, and Vardy’s own style of play, combined to create a scenario where heconsistently overperformed against his stats. Now, you could argue that Vardy is now regressing but, it remains true that, had you been going by underlying stats alone even this season, you mighthave missed out on a run of 14 goals in 12 games.

These statistical anomalies occur at both ends of the pitch. For example, in the past six Gameweeks, Liverpool have allowed more shots than Chelsea and Manchester City, yet they have conceded only a fraction of the goals. Indeed Liverpool have made more defensive errors than all but three other Premier League teams this season and yet they have by far the best defensive record. The fewest defensive errors conceded? Watford.

So, you might surmise from this that you can’t believe stats and you can only really trust your own eyes. But can you actually trust your own eyes? The inherent cognitive biases that can influence an FPL manager’s perspective have been discussed on this site before and they will, in all likelihood, distort our visual perceptions of a player’s performance.

For example, when sitting down to scout a player in a football match, ‘confirmation bias’, or our tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms our existing views or expectations, will almost inevitably come into play.

If you’ve decided that you want a player, you will probably pay greater attention to the good things that the player does. If you’ve decided you don’t want a player, or it’s difficult for you to get them, you’ll probably focus more on the bad things, or dismiss the good things (like a hat-trick) as ‘unsustainable’.

Then there’s the question of the sample size for the Eye Test and ‘belief in the law of small numbers’ which is the biased belief that a small sample will be accurately representative of the larger picture.

Concluding that a player offers attacking threat and thus “passess the eye test” could, in fact, be credited to as little as one or two memorable instances in the match a person just watched, not to mention that it is just one match and that we have yet to factor in the opposition.

Anyone who has watched a football match and thought “Ooh, Luke Shaw is getting forward a lot…” and brought him in on that basis can probably attest to how misleading our perception can be.

The key problem with the Eye Test is the general uncertainty as to what is actually being tested and, even moreso, what it even takes to pass the test. It has no objective standard and, by any scientific measure, the ‘eye test’ would be considered about as reliable as the average office printer.

Stats

So are stats better? Stats do have some advantages over the Eye Test, in particular that they offer a scalable means of interpreting football matches. Stats can distill hours upon hours of football into easily-digestible and objective data, offering a consistent platform for making decisions.

Stats can offer insights that are effectively invisible to the naked eye and help FPL managers to identify undervalued assets, predict form and, indeed, over-performance in a consistent manner. Stats can boil seemingly impossible questions such as; ‘who is the better Liverpool asset; Sadio Mané (£12.2m) or Mohamed Salah (£12.8m)?’ into objective stats, and they can do it in seconds.

Of course, certain stats are better than others. I’ve spoken before in this column about the significance of opportunity over ability for predicting goal scoring form and others have highlighted the strong correlations between stats such as ‘big chances’ and ‘shots in the box’ and goal scoring returns.

Stats such as xG and xGC, while not quite perfect, offer an instructive basis for making predictions and, with the introduction of things such as player heat maps, stats are offering an ever more complete view of a football match.

Stats are also accessible. You don’t need to know your Lindeberg from your Lyapunov or your chi-squared from your psi-squared to make good use of statistical data. This site itself collects, distils and refines stats into many easily-usable forms and offers things like the Rate My Team tool which allows managers to just plug players in and let an algorithm do the rest. Stats in FPL have never been so plentiful, accessible or user-friendly as they currently are.

So, stats are better then? Well, not necessarily as many of the aforementioned challenges that problematise the Eye Test also apply here too. Anyone who has ever run two players through the Comparison Tool has probably experienced the tendency to cherry pick the stats that support the player who, deep down, they really wanted to get in the first place (confirmation bias again).

Indeed, the value of stats are highly conditional; you need to be looking at the right stats, in the right volume and in the right context. For an example of how misleading stats can be, just look at any early season bandwagon and how they came to be thus. Typically they involve people making judgements on a player based on one or two matches with little consideration given to factors such as to the opposition, the player’s level of motivation, the possibility that they are an unknown quantity and thus harder to mark and, broadly, the conditions for sustainability of the form that they demonstrate.

Stats are also very easy to skew. Players who have exceptional games, sendings off, injuries, all these things and many more can disproportionately influence how player or team stats might appear. Despite the developments in xG, I’ve yet to see any stat that can reliably distinguish between a striker having an off day and a goalkeeper having a worldie as well as the Eye Test can, so we’re still some way, I think, to being able to fully and reliably ‘watch’ a match purely in the form of numbers, Matrix-style.

Football, I’d argue, is a much more challenging game to quantify statistically when compared to more linear, turn-based sports such as baseball (which has practically had its genome mapped it is so statistically rich) given the number of variables at play and, while it might seem like there are ‘too many’ stats in FPL, the lack of depth in those stats is actually a pretty big challenge to their utility. In FPL, we are almost always looking to make judgements on sample sizes that would be too small for any valid statistical test. In fact, it’s probably only when we get to this stage of the season where stats offer anything approaching reliability. So, when we talk about stats in FPL, we are really only ever talking about something that is directional and probably never conclusive.

Conclusion

Inevitably, there are advantages and disadvantages to both Stats and the Eye Test and both rely enormously on how we use them and the extent to which we can control the influence of our biases while doing so. Because neither the Eye Test nor Stats can tell the entire story individually, we have to conclude that it is the combination of both that is ideal.

Having said that, I do think that it is significantly easier to remain objective when looking at stats versus a football match because stats tend to provoke far less emotion than the act of watching football does. I also think that we are moving towards a point of sophistication in stats where the marginal benefit of watching football versus just using stats will probably be quite small, possibly to the point where it may even be detrimental from an FPL-perspective.

What do I mean by this? Something people tend to find interesting about my FPL-winning season is that it came despite me watching almost no football at all that year (out of circumstance I stress, not because I don’t like watching football!).

The assumption is, generally, that this would be a huge disadvantage, however, I’ve come to believe that it may actually have been a big advantage. Because I wasn’t watching football, I was able to make all sorts of decisions that I’d normally struggle to make. I never worried about picking players playing against the team I support, I never picked a player because I wanted to feel more invested in a game I was watching and I never conflated what I wanted to happen with what was objectively more likely to happen.

Because I wasn’t watching, none of this really mattered.

Not watching football stripped much of the emotion and many of the biases from my decision process, leaving just the cold hard facts. I wouldn’t want to live like that forever, but I can’t deny that it probably helped that season.

It’s unlikely that many managers will stop watching football for the sake of their FPL team but we can become more conscious of the emotions and biases that might affect our use of the Eye Test, and indeed Stats, for making FPL decisions and seek to manage or compartmentalise these things.

If you use Stats, make sure you’re remaining objective and that you’re looking at the right stats, in a large enough quantity and in context. If you are an Eye Test aficionado, mentally separating the football that you watch for entertainment or team loyalty and the football you watch for research may improve your game. And if you are an Eye Test ‘purist’ who eschews stats entirely, you might want to consider giving them a shot or risk handing an ever growing and ever more accessible advantage to your opponents.

4 years, 8 months agoA decent bench boost, right? Y/N?

McCarthy (AVL)

Lascelles (cry)

Westwood (BOU)

Mooy (shu)