TLDR: I revisited an exercise I ran last year looking at the predictive value of various stats against immediate FPL points returns, adding 2020-2021 data.

Trends established in last year’s exercise have been mostly reinforced with another year’s worth of data. In 2021, we as a community didn’t do quite as well at picking captains in the weekly polls as in previous years when compared with a pure statistical approach.

Most importantly, form (as indicated by both player and team stats) seems to be less important than fixtures (as indicated by opposition defensive stats).

Background and a reminder of the methodology

This article updates, with 2020-2021 data, an FFS article I wrote a year or so ago, in which I undertook a big data exercise to ask a simple question:

If I were to pick my FPL captain based on a single metric, what would that metric be?

In order to answer this question, I shortlisted the most popular captains for nearly all standard (single) gameweeks from the 2017-18 season onwards, and selected from them the stat leaders in various categories: player, team and opposition. I chose the best representative player in each category each week based on stat leaders for the past four weeks. I then went and found out what score the stat leader in each category got in the upcoming gameweek. I also collected data on each captaincy poll winner and RMT leader.

Individual players served simply as the ‘champion’ of that stat scored in that gameweek. The specific player scoring those points became irrelevant as soon as I had ‘converted’ them into points. Of course, quite often a player might be the stat leader in several categories, and may also have been the captaincy poll winner; In this case one player represented multiple categories.

In order not to dilute the dataset too much, and because 90% of FPL players pick from a handful of possible captains (any random 1%-owned player can score 20 pointer and someone would have captained him!) I chose from a shortlist of the 10 players most captained by the FFS community, fewer when the shortlist was smaller. Basically, I was looking at the players who most managers had in their teams and would realistically consider trusting with the armband.

Over time, I gathered a great deal of data on the following categories:

- Captaincy poll – This was self-selecting

- RMT – The same applies

- Player attacking stats – the player in the captain poll shortlist with the most:

- Touches in the box

- Shots

- Shots in the box

- Shots on target

- Big chances

- xG

- xGI

- Team attacking stats – the player ranked highest in the captaincy poll whose team had the most:

- Shots

- Shots in the box

- Shots on target

- Big chances

- xG

- Opposition defending stats – the player ranked highest in the captaincy poll shortlist whose opponent had the worst stats in each of the following categories:

- Shots in the box conceded

- Opposition big chances conceded

- Opposition xGC.

- When the captaincy poll started using opposition shots on target conceded I started adding it as well (past three seasons).

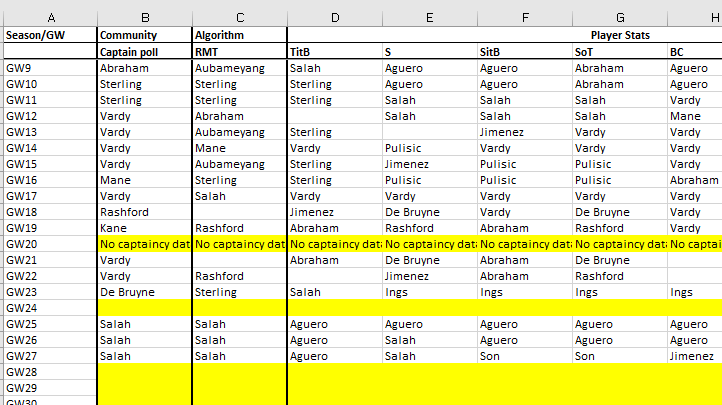

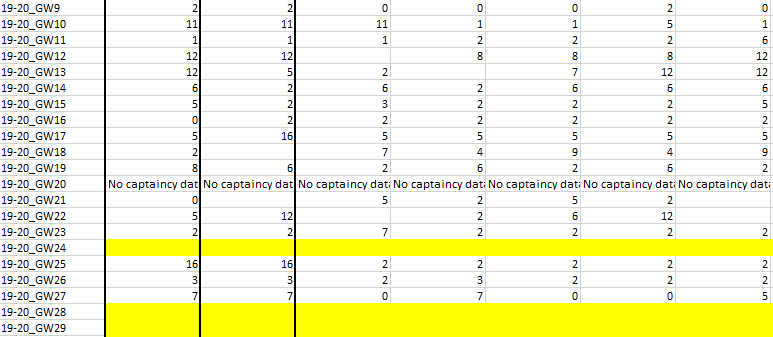

These screenshots show the approach I took (highlights mean SGW/DGW or no data available):

NB:

- The champion for the team stat was the highest-captained player representing that team (e.g if Raheem Sterling had the most votes in the poll, and City led in any of the team stat categories, I would use Sterling’s numbers for those team stats).

- To protect against bias I removed scores of <1 point (red cards, penalty misses and non-appearances) from the dataset to create the so-called ‘tidied’ data from which I based my conclusions. On non-appearances, this tidying exercise also helped to take away some of the bias inherent in my methodology towards the winner of the captaincy poll: the community is good at knowing when a player is going to be rested and is less likely to champion these players (who might then go on to score nothing). The stats can’t filter out players in this way.

- I did not collect data from BGWs and DGWs. These stats are for ‘standard’ gameweeks only. This was to avoid bias (favouring the captaincy poll for DGW/TGW players).

- I only went down ten players in each individual stat category looking for shortlisted captains, and five teams in the team categories. I wanted to capture the best and the worst, i.e., the sorts of factors an FPL manager would want to focus on. If, for example, the captaincy shortlist was made up entirely of Manchester City, Liverpool and Chelsea and none of those clubs scored in the top five in a team stat, I would simply not record a value for that stat for that week.

A fuller explanation of the methodology can be found in the original article posted here.

2020-2021 update

Season context

This was an odd season, being played pretty much entirely under COVID restrictions and without crowds for the most part. COVID also played havoc with some of the fixtures, presenting dataset problems as there were more blanks and doubles (and triples) than usual. This season’s data could therefore be considered a little unrepresentative as the sample size is smaller and the season was atypical. I still collected 287 data points however and it is interesting how much some of the stat categories conform in many ways to the data I collected for the three previous seasons.

As I did not have the time or the organisational skills to check the RMT leader every week, and because this data is no longer presented in the captaincy articles I used to conduct this retrospective review, I was unable to use RMT data for this season. If this is reinstated I will pick it up again in the future. In many ways, it’s not really a dataset, simply an algorithmic interpretation of various datasets, so not factoring it in isn’t a massive problem. It is a slight shame though since my previous article shows it was a consistent predictor of high scores.

Results

Without further preamble, here is the first set of data with this season’s numbers added:

The above table shows the average score, for each season, of the ‘best’ player in each category week-by week.

The ‘best player’ is defined as the most popular for that gameweek when it came to the captain poll (or RMT), or the stat leader in a category in the four weeks immediately prior.

The above numbers are close to actual FPL points, though note that that that data has been tidied to remove data-skewing zeroes and minus points, so the average is slightly higher than ‘real life’ by an average of around 0.4 points across the board. They are not 100% real-world numbers, then, but they are more comparable with each other, which is all we are interested in.

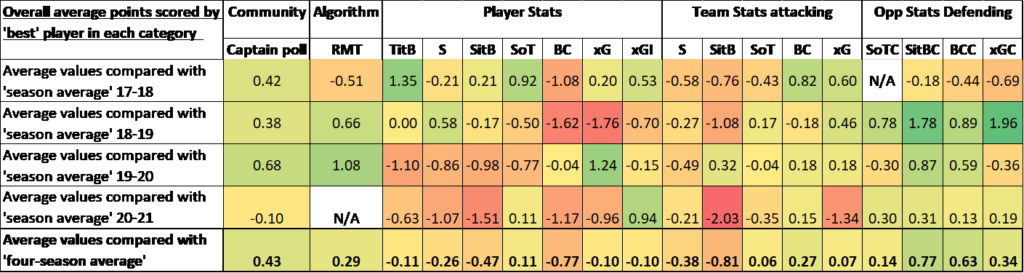

The data can also be represented like this – where zero is the average score for that season for that season’s dataset:

So player touches in the box in the 18-19 season was exactly no better or worse a predictor than an average of all the other stats. Opposition shots in the box conceded and xG conceded did extremely well in 18-19, whilst player xG did extremely poorly in the same season.

So how did this season compare to other seasons? Well, interestingly, despite it being an unusual one, many of the trends established in the past have continued. Picking out the main talking points:

- The captaincy poll is still a reasonably reliable indicator of performance, but returns a negative score for the very first time in 2020-2021: i.e. all of the other stats put together and averaged out perform slightly better. It is still a strong indicator over the entire period.

- Individual player stats remain, frankly, as uninspiring an indicator of immediate returns in 2020-21 as they did previously. Only two (shots on target and xGI) outperformed the average. Player xGI was extremely strong however and is well worth monitoring.

- Team attacking stats took a dent last season. A nosedive in the reliability of team shots in the box and team xG in particular means that this class of statistic is less reliable over all four seasons, albeit not worryingly so. In 2020-2021 All but team big chances (which is turning out to be the most reliable of all of the team attacking stats, looking at all the years combined) underperformed the dataset average, and some of them horribly (looking particularly at team shots in the box).

- It’s worth noting that shots in the box (both player and team) almost invariably underperforms all the shooting metrics. It seems that it doesn’t matter where the player shoots from, and limiting the criterion to whether or not the shot takes place in the box imposes a false restriction on the usefulness of the data. I wonder if this is due to the talismanic nature of the players selected in the captaincy shortlist: they tend to be so skilful and confident that when they take a shot on, they know there is a good chance that the ball will find the net, regardless of pitch position. Perhaps SITB would be a more useful stat for poacher-type finishers from less competent teams.

- Remarkably, considering the fact that the form vs fixtures debate consistently favours form, the opposition defensive stats continue to dominate when it comes to predicting points. Every single stat category outperformed the dataset average for 2020-2021 and on average across all four seasons.

If you had simply chosen the captain poll shortlist player whose opponents were worse for shots on target conceded and shots in the box conceded you would have scored on average 0.8 points more (with x2 applied) per week than going for the most popular captain pick, which is around an extra 30 points per season.

I’m not saying we should be blindly trusting in the data like that, but opposition stats are definitely worth taking into account. Yes, the dataset is small but looking at shots in the box conceded, you would have to go back to the 17-18 season for the best captain as chosen by the community, with all of the data, discussion and eye test indicators available to it, to outperform, on average, the predictive power of this one metric.

The disclaimer here is that as this is a team stat there are more occasions where I had to leave datapoints blank because shortlisted captains didn’t meet my ‘worst five opposition’ criteria. The stats really do look at the worst of the worst and don’t comment on more average opponents. But a similar thing could be said of the team attacking stats – they focus on the ‘best of the best’ and there are also missing values here, and this fact doesn’t help boost some pretty poor averages across the board in that category.

Similarly, one could argue that there is an element of bias in ‘stat champion’ selection for opposition stats, since when there are multiple captaincy poll shortlisted players from the same team (e.g. Sterling 40%; Mahrez 5%) I selected the player with the strongest backing (Sterling), so these stats take into account a combination of opposition weakness and captaincy poll favour. However, exactly the same is true of team attacking stats and as we have already seen, this class of stats is underwhelming. Also, remember that it’s not as if we don’t take stats into account when selecting captains, so whilst captaincy ranking determined how to choose players in certain stat categories, the reverse is also true – we take numbers into account when picking captains.

Conclusions

- Trusting the winner of the captaincy poll is a safe and reliable method of picking a captain. This method regressed slightly in 2020-21 and it remains to be seen whether this picks back up again next season.

- The only reliable player attacking stat is player shots on target. All the others disappoint: they underperform their season’s database averages and are subject to wild fluctuations season-on season. With that said, player xGI performed extremely strongly in 2020-2021.

- Team attacking stats let us down in 2020-2021. All but team big chances underperformed the average. This stat is now consistently reliable over all four seasons.

- Perhaps it’s time to stop looking at shots in the box as a metric entirely or, at least, only using it as a tie-breaker if we can’t decide between two near-identical captains.

- An entire season’s worth of new data has helped to cement the idea that targeting opposition defensive stats remains the best statistical approach to captaincy. At the very least if you can’t decide on your captain and you spot an opposing team giving up a load of short on target conceded, shots in the box conceded and big chances conceded in particular, it is well worth using these metrics to help you make the final decision.

Is form really more important than fixtures therefore? This study doesn’t seem to back that notion up.

Looking ahead / suggestions

Next season, as well as carrying on with this exercise I will also be collecting the immediate returns from all of the stat leaders, not just those shortlisted in the captaincy poll (though they will often be the same). I am particularly interested in focusing on the opposition stats and asking whether it’s best to captain any half-decent attacker playing against a weak side than it is to pick a premium player in form against an average side. I may also try to include a home vs away split but I am yet to decide how this would work, especially as some teams are much better at home, and some are much better away.

If you have any suggestions for further data collection and analysis, please leave them in the comments section below!